22/03/2018

I started teaching technical courses over thirty years ago. At that time, I'd taught similar topics in a university setting and I enjoyed it then as I do now. But I was frustrated by one item on the course evaluations: "Contribution of personal experience." The scores on that metric didn't seem to reflect what I thought I was doing in the classroom. I knew I'd been telling lots of personal stories.

Stories are important parts of technical training and I prefer personal ones. Stories make the content more relevant and personal along with making the presentation more interesting and efficient.

So I set out to try to figure out what I was doing wrong. I decided that maybe I needed to become a better storyteller. I took a writing class at my alma mater that was taught by the late Lois Duncan, a friend of my mom's and a well-known author of young adult books. I read books on storytelling and attended a writing conference. What I learned changed how I deliver training and how the participants in my classes have responded.

One important concept I learned was about the structure of stories. This is where I was coming up short and this is the core of what I want to share with you. I will also be sharing it at the Association for Talent Development's International Conference and Exposition on May 6 in San Diego. I will also share other important story elements including how to build good mental images of scenes and characters.

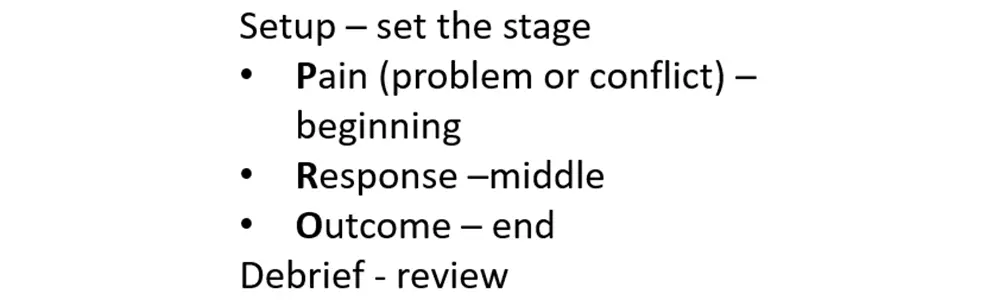

Most people realize that stories need a beginning, a middle, and an end, just like training courses and blog posts. What is critical is what must go into those three parts. First, there needs to be pain or conflict. The main character needs to have some kind of problem to face. That helps grab the readers' interest and gives a reason for the story.

Second, there needs to be an attempt to address or solve the problem. There can be failures - longer stories often have three - and successes. In a training course, I try for at most one failure. We learn a lot from our failures, but stories of just a couple minutes in a course won't really support enough detail in more than one failure for participants to learn from them.

Finally, there needs to be some sort of outcome. I usually try to have the outcome be positive. A negative outcome can be a good learning experience, though: it depends on the story. If the point is "how to do X" and the story boils down to "I did X wrong and here is how I suffered," that can be a powerful message.

I call this structure "PRO". That stands for Pain, Response, Outcome. It is a mnemonic I use to tell stories and I encourage you to use it, too. It helps keep me on track and ensures I don't forget anything. But there is another layer: The story must be framed and debriefed, just like any other activity in a training event or presentation. The framing is part of the introduction. It might be a sentence or two, or it might be longer. It serves to let the listener know why you are telling the story. It might even be a title ("Let me tell you it is important to fasten your seatbelt on an airplane.")

The debrief is necessary to ensure the listeners got the point you intended. When I'm doing a course or facilitating a meeting, I often ask the participants what the story was "about" or why I told it. That gets people more involved and helps the whole group think about the story. I've found that a good story and a meaningful debrief often take less time than explaining concepts the "traditional" ways.

The PRO formula can be used to tell stories in virtually any setting. I use it for impromptu stories I tell in training and facilitation, but you can use it in meetings, speeches, and virtually any setting, including informally with friends. You can use it in your design for stories you prepare in advance, or ones you make up on-the-fly. The point is to use this time-honored structure to tell stories people will remember.

The next time you hear or read a story, look for the pain/conflict, the responses, and the outcome(s). You may find that this structure is everywhere. When properly set up and debriefed, these stories can be valuable learning experiences.

Related Training:

Leadership and Professional Development

Communication Skills

AUTHOR: John McDermott